A 2,000-Year Tradition for the Future The Techniques of Noto Jofu and the Passion of Its Artisans

Noto Jofu, with a history of approximately 2,000 years dating back to ancient times, has been passed down through the Edo, Meiji, and Showa periods, reaching its peak of prosperity. However, as time went on, demand declined. Today, Yamazaki Notojofu Workshop is the only remaining textile manufacturer. We spoke in detail about the charm of Noto Jofu, a craftsmanship so valued that the third-generation artisan once said, “It would be a crime not to preserve such a fine tradition,” as well as the studio’s commitment to continuing the legacy of this unique cultural heritage as the sole weaver.

The Only Weaving Studio Continuing the Tradition and Culture of Craftsmanship

“Noto is gentle, even the soil.” This phrase is said to have been expressed by a samurai from the Kaga clan during the Edo period when traveling through the region, reflecting the kindness and warmth of the people.

The Noto Peninsula in Ishikawa Prefecture experiences its first snowfall around mid-November, and there are many cloudy or rainy days. Despite the harsh natural environment, the people who live here maintain a calm and peaceful demeanor, warmly welcoming visitors.

Produced in Noto is “Noto Jofu,” a high-quality linen fabric woven with threads spun from hemp (asa) in intricate patterns. It is designated as an intangible cultural asset of Ishikawa Prefecture. Currently, there is only one remaining weaving studio in the region that continues the tradition of Noto Jofu: the “Yamazaki Notojofu Workshop.” Around 20 artisans, mainly women, work at the studio, where the sounds of thread spinning and weaving echo from the morning. Takashi Yamazaki, the fourth-generation successor, is a master of “hand-dyeing,” which is essential to creating the kasuri patterns.

The history of Noto Jofu dates back over 2,000 years. It is believed to have originated during the “Age of the Gods,” when Japan was still ruled by deities. According to legend, the princess of Emperor Sujin taught the people of the Noto region how to weave using hemp. Over time, the technique became rooted in the local culture, and it flourished during the Edo period. By the Meiji era, Noto Jofu was even selected as a tribute to the imperial family. In the Showa period, more than 120 weaving studios in Ishikawa Prefecture were producing the fabric at its peak. However, after World War II, changes in lifestyle had a significant impact on the environment surrounding Noto Jofu. The increasing demand for Western clothing led to a decline in kimono usage, and the number of weaving studios gradually decreased. Noto Jofu was even described as a “dying Noto Jofu.” By 1982, the only remaining studio was the Yamazaki Notojofu Workshop.

At this time, it is said that Mr.Yamazaki’s father, the third generation, spoke the following words:

“I believe it would be a sin not to preserve such a wonderful tradition.”

There was undoubtedly a deep respect for the ancestors who had woven this long history and a love for Noto Jofu. However, on the other hand, he also told his son, Mr.Yamazaki, that “there is no need to continue the tradition.”

“The difficulty of managing the business was something my father felt more than anyone else. In fact, there was a time when we couldn’t sustain ourselves solely with Noto Jofu, and we had to make a living by spinning yarn.”

Mr. Yamzaki’s niece, Etsuko Kuse, also recalls that time, saying:

“From a young age, I watched my grandfather work tirelessly to create Noto Jofu. Looking back, I think he felt a strong sense of duty to continue the tradition and preserve the cultural heritage as the last remaining weaving studio.”

Despite knowing the challenges of passing it down to the next generation, the third generation said that not preserving Noto Jofu would be a “sin.” The reason for this lies in the “ultimate beauty created by handwork,” which has been cultivated through a long history. From sourcing hemp thread to weaving it into a single piece of Noto Jofu, every step is done by hand, without relying on machines. The process involves over 100 steps and can take up to a year to complete.

The Masterful Craftsmanship Behind the Delicate Kasuri Patterns

One of the unique features of Noto Jofu is the delicate kasuri patterns created through hand-dyeing and hand-weaving. Additionally, the fabric is known for its translucency, often compared to the wings of a cicada, and its lightness, making it feel almost as if you are not wearing anything at all.

“The kasuri patterns, ranging from geometric designs like mosquito kasuri and cross kasuri to patterns that reflect the landscapes of Noto, such as snowflakes and clouds, appear by precisely weaving the hand-dyed threads. There are over 100 patterns for kimono and more than 50 for obi.” says Mr. Yamazaki.

The dyeing of Noto Jofu does not follow the typical method of tying the threads and soaking them in dye. Instead, the technique primarily used is called “kushi-oshi nassen,” a method unique to Noto Jofu. This technique involves using a comb-like tool and a ruler to directly apply the dye onto the threads. As a master of dyeing, Mr. Yamazaki carefully ensures that the kasuri patterns are aligned, pressing the comb-shaped tool with dye onto threads tightly stretched on a wooden frame. This skilled craftsmanship, which requires a deep understanding of the pattern and the precise positioning of the warp threads, is breathtakingly beautiful to witness. Of course, the finished kasuri patterns are flawlessly executed, exuding both refined elegance and a modern impression.

Mr. Yamazaki further explains by comparing the more than 100 steps involved to the flow of a river.

“If there’s even one mistake upstream, it will affect the weaving downstream. For example, in the upstream process of thread spinning, meticulous and careful work is required to prevent breaking the fine hemp threads, which number over 1,200 for the warp alone. If any thread breaks, a knot forms, and the finish won’t be beautiful. From there, the process continues through dyeing and weaving, like the flow of a river. While each artisan focuses on their own work, they also remain mindful of the next artisan’s process. It’s a task that relies on teamwork.”

Weaving Tradition and Innovation,

The Value of Noto Jofu That Resonates in Modern Times

In recent years, 2 to 3 new weavers have joined the Yamazaki Jofu Workshop each year. In the world of traditional crafts, where many businesses struggle due to a lack of skilled artisans and the risk of losing the craft, this is quite a rare situation. One of the driving forces behind this is social media.

“Many people have developed an interest in Noto Jofu through our social media and have visited our workshop on their own. I believe they resonate with our philosophy as well.” says Ms. Kuse.

Craftsmen who wish to inherit the tradition of Noto Jofu knock on the studio’s door and spend 2 to 3 years carefully learning the weaving techniques. As they gain experience, they come to understand the unique characteristics of hemp thread, which changes with temperature and humidity, and develop their skills. During this time, Mr. Yamazaki always tells the artisans, “Imagine who will wear the finished piece.” The thought and care put into each creation further enhances the value of Noto Jofu.

In 2021, Yamazaki Notojofu Workshop launched a new in-house brand, “Noto Jofu YAMAZAKI NOTOJOFU,” offering not only expensive kimonos and obis but also accessories such as scarves and small items, making Noto Jofu enjoyable for everyday life. The brand’s logo features an arrangement of the kimono collar and a crosshatch pattern. It expresses the wish to preserve traditional craftsmanship while incorporating Japanese culture and Kasuri patterns into modern life.

At the same time, they reassessed their previous distribution channels and began efforts to deliver their products directly to customers. Ms. Kuse, who is responsible for the company’s public relations and product planning, says the following:

“In recent years, we have been attending department store events with ‘Noto Jofu YAMAZAKI NOTOJOFU’ products. Customers who experience Noto Jofu for the first time have given us great feedback, saying they can easily incorporate it into their everyday lives.”

As someone who is aware of her role as a “messenger,” Ms. Kuse places great importance on communication with customers. She carefully explains the artisans’ processes to the customers. Furthermore, when she returns to the studio, she always shares with the artisans emotional feedback from customers who have experienced the products. This is something she values deeply, as it helps convey the feelings and thoughts behind each piece.

Furthermore, Yamazaki Notojofu Workshop’s challenges continue. In an effort to convey the comfort of Noto Jofu, which can only be truly appreciated when worn, they launched a special daily wear fashion brand, “RINSO,” the following year. The collection, which includes shirts, jackets, and pants, incorporates elements of traditional Japanese design into Western-style clothing, reflecting the aesthetic values cultivated by traditional culture in modern fashion. Many people, including those who are encountering Noto Jofu for the first time or who don’t typically wear kimonos, have praised the unique texture of the linen and the beautiful translucency created by the handwoven fabric.

“The most important thing is to convey the value of Noto Jofu. Even if the form of the products is different, we focus on creating items that allow people to experience the beauty of the kasuri patterns and the translucency of handwoven fabric.” says Ms. Kuse.

The launch of “Noto Jofu YAMAZAKI NOTOJOFU” marks a new step for Yamazaki Notojofu Workshop. It has become a valuable opportunity for modern-day Japanese people, who rarely have the chance to touch or wear kimonos, to connect with traditional culture. Moreover, there are instances where people from countries without kimono culture purchase “RINSO” as well. The beauty, texture, and undeniable quality of the products transcend language barriers.

Overcoming the Earthquake and Resolving to Create Genuine Craftsmanship for the Future

Just then, the Noto Peninsula earthquake struck. Ms. Kuse, who arrived at the workshop 30 minutes after the disaster, witnessed the scene of shattered showroom glass scattered across the floor and many machines that had fallen over on the second floor of the workshop.

“However, we were able to resume work in the workshop after about a month. I am deeply grateful to the artisans who, despite having been affected by the disaster themselves, worked tirelessly to continue their craft. What I can do now is to help more people get to know Noto Jofu and protect the artisans in front of me. When I think of my grandfather, who continued to work hard as the only weaver, I feel that my role is to create an environment where the artisans can work comfortably. Noto Jofu exists because of the artisans. Both my uncle and I hold this value dear.”

Finally, I asked Mr. Yamazaki about the future of Noto Jofu.

“As someone born and raised in Noto, everything I envision is filtered through the lens of Noto. The beauty of nature, the sincerity of the people—everything shapes my sensibility, which is expressed through the works. Moving forward, my mission may be to continue creating ‘good craftsmanship’ together with the artisans, always valuing that sensibility.”

The skills passed down by artisans here in Noto for over 2,000 years are embedded in each piece of Noto Jofu they create. Through their hands, the determination to carry on genuine craftsmanship into the future is also woven into every fabric.

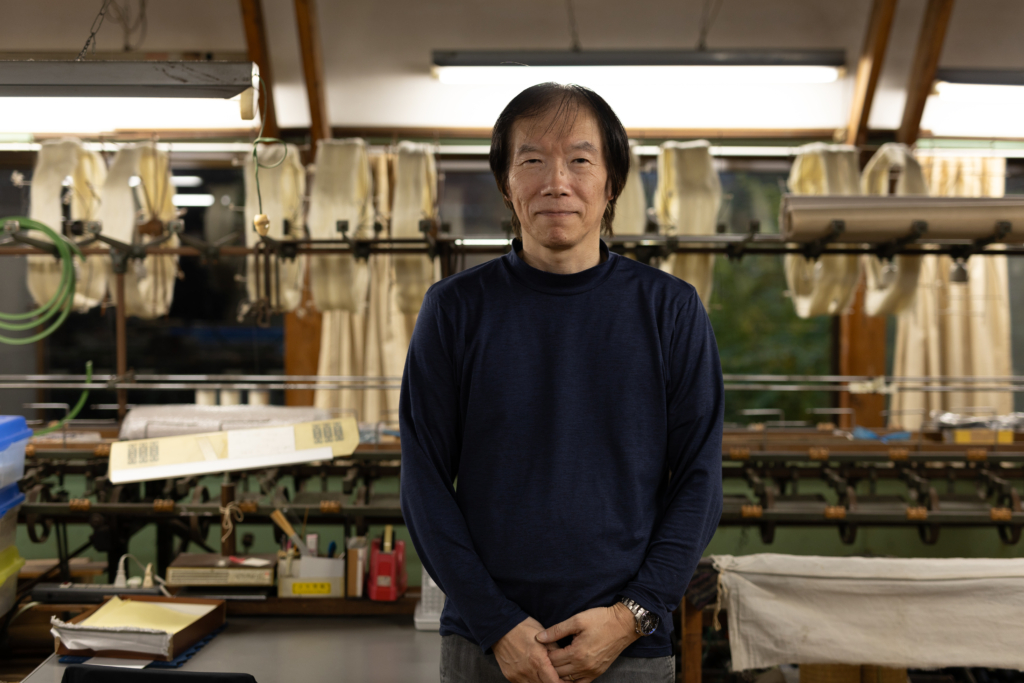

Yutaka Yamazaki

A fourth-generation textile weaver from Hakui City, Ishikawa Prefecture, and the CEO of Yamazaki Notojofu Workshop. In his mid-40s, he left his career as an electronics manufacturer to take over the family business. Since then, he has developed his skills and now leads the studio, handling pattern planning and design while also serving as a skilled artisan in the hand-dyeing technique essential for creating kasuri (ikat) patterns.

Etsuko Kuse

From Kanazawa City, Ishikawa Prefecture. Executive Director at Yamazaki Notojofu Workshop. She grew up watching the work of her grandfather, a third-generation artisan, and developed an interest in his work. After graduating from university, she worked in content creation and preservation at a national museum in Osaka. Currently, she is responsible for sales, public relations, and product planning, serving as a “communicator” who proposes the value of Noto Jofu, aiming to ensure it remains loved and connected to the future.

If you would like to visit the Yamazaki Hemp Fabric Workshop and get further into the world of Noto Jofu, please see the following information

Noto Jofu, the finest hemp fabric handed down from the divine era Special visit to the workshop where summer kimonos are produced

Highlights

・You will have a special opportunity to see the workshop where the finest traditional summer kimonos have been produced for generations.

・After visiting the workshop, you can see the actual fabrics and kimonos in the gallery.

・After visiting the workshop, visitors can see the actual cloth and kimono in the gallery and purchase original goods made of Noto Jofu.

Information

Price: from 4,000 yen per person

Participants: 1 to 6 people

Duration: about 1.5 hour

Included: Workshop tour fee

Meeting: Parking lot of Yamazaki Hemp Fabric Workshop

Language: Japanese (English interpretation service can be arranged upon request)

For reservation inquiries, please click here.